“The urban…is a promiscuous, evolving manifold, to be distinguished whenever possible from the term ‘city,’ which, in its saddest form, may consist of nothing more than a stillborn, mechanical, man-made design.”

-Sanford Kwinter

People who live in New York enjoy talking about New York, to everyone else’s frustration: what it’s like to live there, or how different New York is from some other city. People who have recently moved to New York are often the worst offenders, being most acutely aware of the contrast between their new environment and whichever one they left. The eventual product of all the hot air spent explaining New York is a narrative that becomes true because so many people believe it is. New York transmits that narrative to the rest of the world via the media for which it’s a nerve center, and if the rest of the world doesn’t quite care as much as New Yorkers imagine, then that’s the rest of the world’s secret. The mythology of New York is a self-fulfilling prophecy and powerful reality, though: People move to New York primed to live in ways that may have been impossible or unrewarding anywhere else.

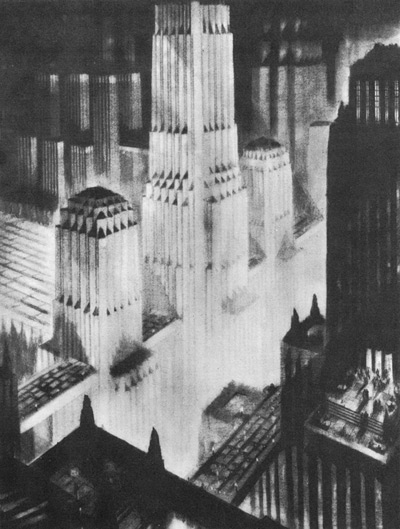

The mythology just described is precisely what Rem Koolhaas calls “Manhattanism” in Delirious New York. For him, however, Manhattanism is more than just mythology—it’s the cultural reflection of the bricks-and-mortar city. What Koolhaas calls New York’s Culture of Congestion—a product of the city’s density, its verticality, and its entirely unnatural, man-made built environment—finds its origin and synthesis in the skyscraper, the focus of DNY’s second chapter. The skyscraper would evolve into “a machine to generate and intensify desirable forms of human intercourse,“ and as it emerged in the early decades of the 20th century, Manhattanism emerged as well.

Brian Eno experienced New York in a similar way to Koolhaas, offering his own take on the Culture of Congestion in his essay “The Big Here and the Long Now.” Eno recounts visiting a wealthy friend’s apartment for dinner in 1978 and being shocked by the contrast between his friend’s multi-million dollar residence and the decaying building and neighborhood in which it was located. To Eno’s friend, the idea of “here” encompassed a tiny area—the room itself and nothing outside of it. The “Small Here,” as Eno describes New Yorkers’ hyperlocal attitude toward space. He continues:

“I noticed that this very local attitude to space in New York paralleled a similarly limited attitude to time. Everything was exciting, fast, current, and temporary. Enormous buildings came and went, careers rose and crashed in weeks. You rarely got the feeling that anyone had the time to think two years ahead, let alone ten or a hundred. Everyone seemed to be passing through. It was undeniably lively, but the downside was that it seemed selfish, irresponsible and randomly dangerous.”

Eno and Koolhaas both see a dark side to Manhattanism, but one cloaks his sense of foreboding in perverse fascination while the other seeks an alternative.

Good or bad, Manhattanism is no longer confined to New York. Born on its eponymous island in the 20th century, has since spread throughout the world. It is a version of the urban that came from the city but no longer needs the physical city to flourish. Last week, the New York Times profiled Joe Weisenthal, the lead financial blogger for Business Insider, providing evidence that the digital universe pushes Eno’s Small Here and Short Now to even greater extremes. As the profile tells it, most of Weisenthal’s waking life takes place on the Internet, especially on Twitter. His “here” does not extend beyond the devices he’s using to communicate; his “now” is minutes or even seconds. At one point, he DVRs “between 8:28 and 8:32 on CNBC” and asks his Twitter followers not to tell him what happened. Likewise, the financial firms he writes for and about are extending cables across the Atlantic to get information milliseconds sooner. Neither Koolhaas nor Eno could have anticipated these conditions but they represent the culmination of what both men described decades ago. Last century, the skyscraper was the machine that “intensified desirable forms of human intercourse.” Today, we have developed many more machines to do the same.