Cars, Clothes & Battlesuits

December 13, 2016

Cars belong near the top of a long list of reasons why America is the way it is, but one American quality I’ve never heard attributed to cars is our increasing casualness of dress, which seems to have mirrored our impulse to drive during the past century. There’s no obvious connection between the two phenomena, yet whenever I leave New York for a more American part of America I remember that the city where we drive the least is also our least casual and I wonder if cars are somehow the cause.

Sweatpants, flip flops, sneakers, t-shirts, and baseball hats have pervaded nearly every realm of life except for weddings and funerals, slowly conquering former bastions of formality like the workplace. Technology has been a factor: Watches are mere jewelry now thanks to the digital clocks that accompany us in our phones, but more broadly than that specific side effect, all technology, in a sense, clothes us, augmenting our natural faculties and our bodies. Clothing itself is a technology—Marshall McLuhan called it an extension of our skin that stores and channels energy, an increasingly tactile shell that (especially in America) overthrew the more visually-oriented attire of aristocracy.

For McLuhan, clothing and housing are two different layers of our technological exoskeletons. The city is yet another layer. If the human body moves through the world encased within a protective stack including these components, surely the car has a place in that stack as well, somewhere between the clothing and city layers. Furthermore, we should observe significant cultural differences where any of the layers is minimized or absent altogether, with adjacent layers intensifying to compensate. This is my theory of clothing’s amplified role in New York, where the car layer is anemic compared to elsewhere. When I visited my hometown of Indianapolis over Thanksgiving I didn’t bring a coat with me, knowing that I’d spend all my time in my house or in a car, save for short walks across parking lots. “My car is my coat” was a dumb joke I made. I found myself wondering why anyone who has a car would bring their coat on most errands, or even own an expensive one for daily life.

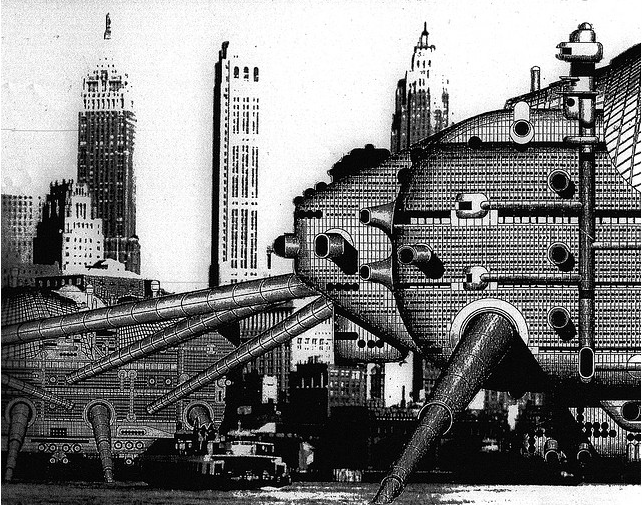

Archigram’s “Walking City” (source)

The more layers that encase us, the less is demanded of our bodies themselves. To follow this dynamic to its logical conclusion is to end up with inert humans hibernating in the fluid-filled pods of The Matrix, naked and fully immersed in an advanced technological stack, wrapped in the multiple layers of protection it offers. Wearing sweatpants and spending whole days surfing the internet is not entirely different from that extreme scenario, while traditional urban fabric seems anachronistic by comparison: Walking outdoors on the streets of dense cities, we’re vulnerable and suboptimized, clad in boots and coats rather than temperature-controlled pods of the automotive or Matrix variety.

If cities are an outer protective layer in this ecosystem, on the other hand, maybe we’re not so vulnerable after all—see Matt Jones’ 2009 blog post “The City is a Battlesuit for Surviving the Future,” arguing that the outer urban shell is the most important layer of all. The post’s title refers to Jack Hawksmoor, the protagonist of Warren Ellis’s comic book The Authority, who wraps himelf in the city of Tokyo to fight a sentient, time-traveling version of 73rd-century Cleveland. Jones observes that we increasingly wrap ourselves in the city as a defense against all the forces of nature that have assailed humanity throughout history, and in the networked present and future, this can become more true than ever. Jones writes, “The city of the future increases its role as an actor in our lives.” A stronger outer shell, the city, might then enable a more humane life within, while a compromised city layer shifts its functions onto the house and car layers, dividing its inhabitants into more atomized enclaves.

The networked city Jones describes is a different animal than its forebears, and is somehow more tactile than even McLuhan anticipated. We now inhabit the meatspace city, whose previous functions of information exchange have increasingly migrated to digital channels (which are, of course, embedded in its physical fabric). The features of traditional urbanism most likely to intensify under this new regime, to the extent that it continues spreading, are the most difficult to encode: eating, drinking, shopping for specialized merchandise, and the more precious types of human interaction. The meatspace city is a construction of affluence and is far from ubiquitous—it might never be—but even it presents a more comfortable and convivial interior than the car in the suburban wilderness. We’ve lost some of the optimism about networked urbanism that we enjoyed in 2009 when Jones wrote his battlesuit piece, but many of the reasons for that loss are pervasive and only most visible in cities, which are still better armor than most of the substitutes we’ve tried.